Former Commerce Department Economist on AI’s ‘Great Potential’ to Boost Labor

A top economist shared how AI is changing the labor market — and what workers can do today to succeed.

Since ChatGPT’s debut in 2022, the future of work has emerged as a lightning rod issue across virtually every sector and walk of life. While it’s clear that artificial intelligence (AI) will fundamentally reshape the way we work, the specifics are still shifting into focus. What will be the true impact of AI on jobs? How should workers ready themselves for an AI-enabled future?

These were among the questions that were top of mind at Salesforce and Eurasia Group’s recent Global AI Leadership Summit in New York City. To learn more, we caught up with panelist Jed Kolko, former Under Secretary for Economic Affairs at the U.S. Department of Commerce in the Biden-Harris administration. Kolko has more than 20 years of experience as an economist, working for Forrester Research, the Public Policy Institute of California, Trulia, Bloomberg, and Indeed.

We chatted about AI anxiety, the state of the labor market and his first job in high school as a “human Google News alert.”

How do you see generative AI changing the labor market?

Jed Kolko: One thing that may be different about gen AI versus previous waves of automation or technological change is that it’s a wider set of people whose jobs or tasks might be directly affected, including more people at higher levels of education and technical skill. And that changes the public perception, the types of concerns, and how it’s portrayed.

Gen AI has more of a potential to affect creative jobs – jobs that 10 years ago were outside the automation discussion, but now are very much part of the gen AI discussion. And of course, when you have jobs like “journalist” and “screenwriter” potentially affected by gen AI – these are the people who help explain and imagine the economy and society to the rest of us and who influence how people talk and think about technology.

There’s always a degree of fear and uncertainty associated with the rise of new technology. Where do you think that comes from?

JK: I think it’s much easier to imagine the jobs that exist today that might be threatened, than it is to imagine jobs that don’t exist today that could exist in the future. It’s very hard to predict the kinds of jobs that people might be doing 10 or 20 years from now that don’t exist today. My first job in high school, I worked in my local State Assemblywoman’s office, and I would look for and clip newspaper articles about her. I was a human Google News Alert. That is a task that no longer exists manually, and whoever does that job today does a very different set of tasks than I did.

You served as Under Secretary of Commerce during the watershed rollout of ChatGPT. What was the initial reaction in Washington during those early days in 2022?

JK: Part of my role was overseeing the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, as well as the department’s Chief Data Officer. One question that our bureau thought about was how AI might affect the information people get when they write prompts about the economy, or about economic and other statistics. We need to ensure that when someone types in a question — whether it’s into a search bar or as a prompt — and they’re asking about how many people there are in the U.S., that they are getting the right answer, that it is the official and current Census Bureau estimate of the population.

That’s a very specific example, but in general, AI means that anyone providing data needs to look closely at how it’s being tagged, so their data is surfaced appropriately by AI when it should be.

What excites you most about AI as an economist? And what worries you?

JK: I think AI has great potential to both raise the rate of innovation and productivity, and help give more people access to information that helps them be more productive, or creative, or both. But I think there are many challenges. Access to Gen AI – and nearly every technology – is unequal. Even within the U.S., many people don’t have good broadband access, many people don’t have computers. Many people don’t have the technical literacy to craft a good prompt.

And so there are lots of underlying divides, digital and otherwise, that get in the way of everyone being able to access this.

How would you compare this moment to other major inflection points in recent history?

JK: I think there are a few key differences today versus 20 years ago in how we think about technological change. One is that demographics are different. The population is older, on average, than it was. A much higher share of the population is of retirement age. The workforce is growing more slowly. And so for all the concerns about jobs that might be threatened by technology, there is the countervailing concern that the workforce isn’t growing very fast, and we don’t have the same population of younger people entering the workforce learning new skills. In other words, while Gen AI might affect labor demand, we also now must think about labor supply.

Within the U.S., there’s also been growing geographic inequality, where the gap between richer places and poorer places has widened. And there has been increasing concentration, particularly of high-paying, more innovative industries, in particular places.

One of the areas of focus from the Biden Administration has been trying to create new tech hubs in other parts of the country to combat some of this growing geographic inequality, focusing on places that have been left behind. That’s a big change from 20 years ago.

For a lot of workers, the sentiment around AI right now is equal parts excitement and trepidation. What advice would you give for people to make the most of this opportunity?

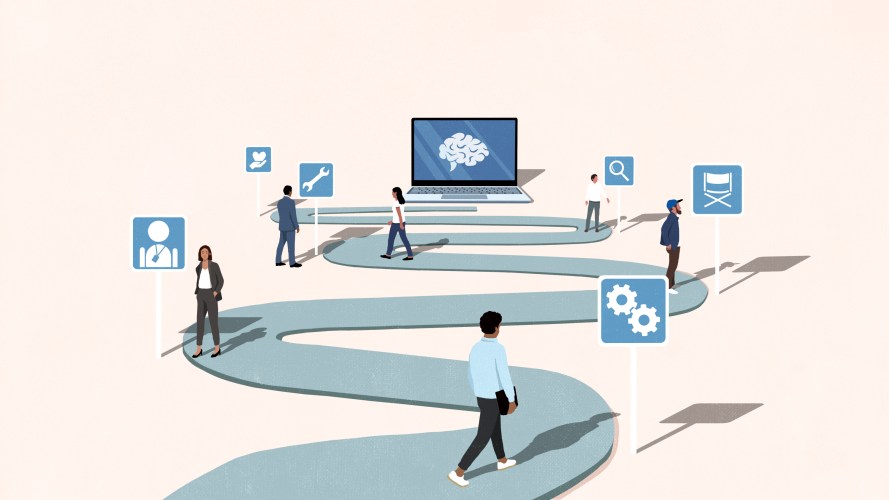

JK: For most of us, we are much more likely to be users of AI rather than creators of AI. And so the important skill for most people is not learning how to code, but rather learning how to use today’s and tomorrow’s tools. 10 years ago, that might’ve been learning how to use digital calendars, or Excel. Today, that might be understanding what makes for a good prompt, or being able to think about what are the parts of your job that could be done more efficiently, or could be automated, so that you can start practicing how to use AI tools to do that better.

I think the other thing is, if you’re in the position of having to make a transition, because you’ve been laid off, your occupation’s threatened, or whatever the reason is, often people imagine making big leaps or starting completely different second careers. But most successful job transitions are to adjacent kinds of jobs that have a lot of overlap in the skills that you already have.

Lastly, I think one of the trends that we’ll continue to see with AI, and technology more generally, is that there will increasingly be projects that involve someone on the engineering side, someone on the product side, someone on the legal side. And you’ll need someone who can translate among them and speak all those languages. I think lots of organizations have those gifted translators, but it’s an underappreciated or unacknowledged skill. It can be hard for people to see that in themselves and I think it’s often a skill that’s not listed in a job description, but it’s incredibly valuable, and will only become more so.

Learn AI’s A-B-Cs at Dreamforce

Are you prepared for the jobs of tomorrow? Get ready today by registering for Dreamforce, Sept. 17-19 — in person in San Francisco or streaming on Salesforce+.