Engaging the C-suite With Customer Experience

Engaging the C-Suite with the Customer Experience

Sponsor Perspective

At Salesforce, our global research finds that customers, everywhere, expect more today from the brands that enable and enhance their lives. Customers expect an experience that feels highly personalized, and they’re not impressed by technobabble like “AI.” If it doesn’t feel like magic, it’s insufficiently advanced.

When even basic products perform like the premium models of yesteryear—compare a $10 quartz watch to a $10,000 Swiss chronometer, and guess which keeps better time?—then the battleground of competition shifts from the “product” to the customer experience. Moreover, a company does not merely compete against others that sell similar things: today, the best experience anywhere is soon the expected experience everywhere.

Even in business-to-business markets, which used to be considered a realm of nothing but price and delivery and specifications, people now expect much more. If it’s hard to do business with a company, customers can easily find alternatives. At best, an experience-poor provider can compete on price alone, and see margins and profits erode; at worst, it can suffer mass defections.

What’s needed is sometimes called a “digital transformation,” but many interpret that label as meaning the adoption of technology. It is at least as much about innovation at the level of process, not just modernization of the process already in place. Doing what’s become the wrong thing at lower cost, with higher speed, is still doing ...the wrong thing.

In support of the right thing, Harvard Business Review Analytic Services has conducted a deep dive into the challenges that companies face as they embark on the kind of digital transformation that is focused on customer experience. Readers should note that this depends, crucially, on creating cultures where customer-focused innovation can thrive. This report, as well as research by academics Scott Page (University of Michigan), Alex Pentland (MIT), and others, should serve to underscore how diverse teams are key. The more diverse the team, the more transformative the innovation.

Diversity, moreover, no longer means just equal representation. As noted diversity advocate Verna Myers puts it, “Diversity is being invited to the party. Inclusion is being asked to dance.” Without inclusion, the crucial connections that attract talent, encourage participation, foster innovation, and lead to business growth don’t happen.

The need to make technology and departmental silos a thing of the past is a key theme in the narrative ahead. Customers expect a company to know them, and to build on their history of past interactions. Customers expect companies to provide what they need on any channel, and to let customers move from channel to channel without having to repeat themselves. These are the table stakes of digital transformation.

Raising the stakes still further, though, are accelerating changes to workplace culture— but changing how a company operates is not an easy task. The pages ahead focus on organizational change management: identifying change advocates, understanding the benefits they derive, and examining the results that they’ve championed.

It’s a new world for companies, more competitive than ever before. The sense of urgency to change or to lose both margins and market share, has never been greater. A decisive factor will be a company’s ability to achieve a digital transformation of customer experience.

Highlights

Business leaders are turning to these and other practicable approaches to digital transformation.

Pushing silos into the background when cross-functional work is needed.

Modernizing many legacy IT systems through use of artificial intelligence.

Understanding that important trends can be detected even with “messy” data.

The digital dust is beginning to settle when it comes to organizations gaining a deeper understanding of how to track changing customer expectations and how to deploy technologies to meet those needs. Forget blowing up business models and ripping out IT systems. There are more practicable solutions for the CEO to direct his or her organization to use to improve the customer experience.

Although companies in some industries may have to take dramatic measures, business leaders in many other sectors are developing and implementing readily applicable and straightforward approaches that keep digital transformation efforts moving when it comes to satisfying customer demands.

In this report, we explore the new solutions and approaches that are emerging that address many of today’s most vexing digital and market challenges. Executives are increasingly able to push silos into the background and not let them stand in the way of their banding together to meet customer needs. The growth of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics is making many of the challenges of legacy IT systems moot through those technologies’ ability to modernize the customer service infrastructure. Approaches to change management are becoming significantly more focused and faster. Moreover, companies are implementing systems and processes that help them spot changing customer needs and give them the confidence to move forward with solutions even if they have messy data.

At the vortex of this problem solving—as examples ahead illustrate—should be a leader who makes sure that approaches aren’t too granular or too specific to a particular line of business while optimizing a wider set of technology priorities for the organization. “There has to be complete alignment between CIOs, CTOs, CFOs, CMOs, and others in the C-suite,” says Brad Wilson, chief marketing officer at the online lending exchange LendingTree. “Where I see these efforts hiccup or fall down is when this alignment isn’t in place.”

Making Silos Irrelevant

Business leaders often gnash their teeth over the human tendency to band together into silos and avoid working with other parts of the organization. Silos can make it nearly impossible for companies to gain a full picture of how technology can meet higher customer expectations. The reality is that businesses will always have to have some structure, which inevitably creates silos. And there are instances where having information silos is necessary.

Some businesses, however, have learned how to make silos irrelevant when cross-functional work is needed. A 2018 Harvard Business Review Analytic Services study found that executives and managers with the greatest success in implementing such strategies say that their company structure helps. Those who are less successful say that their company structure gets in the way. Curiously enough, both camps are using the same or similar structures, complete with silos.

“It’s clear that some companies have CEOs who know how to fight back against silos,” says Ethan Bernstein, the Edward C. Conard Associate Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. “They know how to foster collaboration and that it is about much more than the spirit of teamwork.”

Pushing silos into the shadows starts by eliminating perverse incentives, according to Amy Edmondson, the Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School and author of The Fearless Organization. “Company leaders will often call for collaboration, but then evaluate, compensate, and promote employees based primarily on their individual accomplishments,” she says.

Incentive systems need to reflect the collaborative goals of the organization and motivate people to reach beyond their silos. For example, if a company is trying to get different parts of the organization to band together to improve the customer experience, individuals working on cross-functional efforts need to be measured against the success of those improvements.

Otherwise, individuals will fear that if they share good ideas, they may not receive any credit for them—and may even be sanctioned for unpopular ideas.

Formal incentives are only the starting point, according to Edmondson. Collaboration needs to be open and robust if multiple perspectives are to come together to address customer needs. To create an environment of candor, companies need to establish what Edmondson calls a fearless organization. Simply put, a fearless organization provides a psychologically safe environment where people don’t shy away from expressing their thoughts and observations—good or bad.

To create psychological safety, company executives and managers should model genuine curiosity about the business and respect for what people have to say. The most effective means to that end, according to Edmonson, is to embrace “situational humility.” Individuals are reluctant to offer opinions and suggestions when they perceive that their managers feel that they know everything. In today’s volatile business environment, not knowing everything should not be interpreted as a lack of confidence, but rather as evidence of clear-eyed recognition of the challenges ahead; effective managers don’t pretend otherwise, potentially blocking out constructive information. Executives should be perfectly comfortable seeking advice and pointing out when they don’t know something. Modeling this behavior will spur others to be more candid, which will enliven collaboration. Such a tack also relieves one of employees’ greatest fears—that there are negative consequences for speaking up or coming up with an idea that ultimately doesn’t pan out.

Boston Scientific, a global medical device company, has heeded much of this advice and significantly weakened its silos. “Our divisions have a great deal of autonomy,” says Jodi Euerle Eddy, Boston Scientific’s senior vice president and CIO. “We have pushed decision making much closer to customers and markets.”

Although decentralization made silos less formidable, Boston Scientific still has them. To push them more deeply into the background, the company has been introducing small agile teams throughout the organization. The teams include IT, marketing, and business unit members. To make them a center of cross-functional, customer focused energy, agile teams have full decision rights on what to implement, how, and when.

The empowerment and success of these teams struck a nerve inside Boston Scientific. The company has been able to expand them into a dozen digital health studios, attracting employees from all parts of each business. Corporate-level functional units, such as IT and marketing, serve as centers of excellence that provide expertise to functional professionals housed in business units. Business unit professionals form a bridge to their corporate counterparts, thus eliminating much of the siloed behavior found when functions stand alone and are autonomous.

To create an environment that encourages sharing ideas, Boston Scientific focuses heavily on diversity and inclusion. “People feel like they are really part of things and have a voice,” says Eddy. “When people are confident that their voices will be heard, they are much more likely to open up.”

The company also pays close attention to compensation and rewards as a means of stimulating cross-functional behaviors. “Compensation is heavily skewed toward overall corporate performance,” she says. “That encourages people to work together and solve customer problems.”

Changing How We Change

A key element of Boston Scientific’s culture is playing a major role in pushing silos into the background. “People work here because they want to save lives,” says Eddy. “That really drives everyone to work together.”

Few organizations hold the same cultural advantage as Boston Scientific does, and change management approaches designed specifically for fast, volatille business environments don’t work very well, either, on a wholesale scale. A more gradual change management strategy is often required. “Executives often believe they have to change the entire culture in order to be effective,” says Jon Katzenbach, managing director at Strategy & Katzenbach Center for Leadership and Culture and author of The Critical Few. “But changing an entire culture can take decades. And most businesses don’t have that much time.”

Through his work with Strategy& (now part of PwC), Katzenbach discovered that companies can change what they need to change in as little as one year. The secret is not trying to replace the current culture with a new one. Instead, executives should identify positive emotional feelings that already exist in the current culture and that will support the behavioral changes that are most critical to success.

Meg Whitman at Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) is a case in point. When she took the helm of HPE in 2015, she had her work cut out for her. The organization was immense, complex, and siloed.

Whitman needed employees to work together and accelerate innovation in operations and product development so that HPE could better connect with customer demands. Attempting to change the culture of such a large institution would probably have failed. Instead, Whitman anchored her strategy to an important element of the HP culture that went back to the company’s very early years—the HP Way.

Although the HP Way seemed dormant, it was still considered important by many employees. The HP Way encouraged several behaviors that were critical to the company’s success as it faced competitive challenges from all corners. For one thing, the HP Way placed a premium on teamwork. It also encouraged people to walk around, which was a proven way to stimulate idea-sharing across company boundaries.

Collaboration was seminal to meeting rapidly changing customer expectations and business environments. Whitman realized she needed the culture to be an asset to her effort to overhaul HPE and that she couldn’t change it completely over any reasonable period. As a result, she recast the initiative as the HP Way Now, which described the core behaviors in the current context of digital business.

In lieu of a massive cultural overhaul, Katzenbach says companies should first identify specific behaviors in the organization that need to be changed. The targeted behaviors should be focused on important business outcomes and be limited to just three or four. Then company leaders should find three or four sources of already existing positive emotions that would convince people of the reasons to change. To put the process in play, Katzenbach continues, a business should seek out the company’s emotional sensors— individuals with high degrees of emotional intelligence and a finger on what people believe. These individuals often enjoy the respect of their peers and superiors and thus can be powerful change agents.

In his book The Critical Few, Katzenbach describes how General Motors’ former CEO, Fritz Henderson, pursued the path that Katzenback is describing when he was charged with bringing the automaker out of the bankruptcy it declared in 2009. “Henderson was frank about the fact that he didn’t have 10 years to change the culture,” Katzenbach recalls. “He needed to move fast if GM was to survive.”

Accelerating decision making was a key behavior Henderson needed. To rush that process, he eliminated several layers of bureaucracy and empowered managers on the front lines to make more decisions. To get buy-in for these significant changes, he leaned on an implicit part of corporate goodwill—being part of GM was like being part of a family. It was a localized feeling where employees felt responsible for each other, especially when the company’s performance threatened everyone’s livelihood. Henderson created a council to spur the needed changes. Members were drawn mainly from the front lines and had been with GM many years. The car manufacturer eventually emerged from bankruptcy and was able to repay the U.S. Treasury for the money given to it in the form of a bailout. Focused behavioral change played a major role in the company’s turnaround.

The New Legacy of Legacy Systems

According to Metzger, many legacy systems can be modernized through robotic process Automation (RPA) and artificial intelligence(AI). These technologies can be much less expensive than manual system replacement and they reduce the disruption to business during the process.

RPA and AI can be used to connect systems that otherwise don’t speak to each other. For instance, a business with customer and performance data scattered across systems can use a bot that pulls data from different systems and then performs needed analysis. Using RPA and AI in this way can readily improve the quality and frequency of critical reporting to support decisions. Similarly, if the company’s data management practices have standardized how customers are entered into different systems, companies can use bots to help conquer the seemingly intractable challenge of creating a single view of a customer.

Consider what the C-suite at the online lending exchange LendingTree is doing in grappling with old email distribution technologies that on their own can’t increase the speed and personalization of email outreach. The company is using AI to augment the speed and personalization of its email outreach.

Prior to the use of AI, a marketing manager would have to determine prospects and what to offer them and then pull lists from an existing system. The lists would then have to be manually exported to another system that creates and sends email promotions. Now, according to LendingTree’s Wilson, bots pull the lists and move them to other systems. But they can do much more than that. To increase the precision of personalization, LendingTree has added AI to the mix. AI helps improve targeting and choice of the next best offer by learning and analyzing the results of each mailing.

Some systems will have to be replaced, of course, but Deloitte’s Metzger urges companies to avoid wholesale rip-and-replace efforts and go with a more structured peel-off process based on how important specific new capabilities are to the enterprise. “Companies should start by defining what big changes are needed in how the company operates and how it will meet the needs of its customers,” he says. “Then they need to inventory all the systems they currently have and how they are connected to determine the modernization or replacement priorities.”

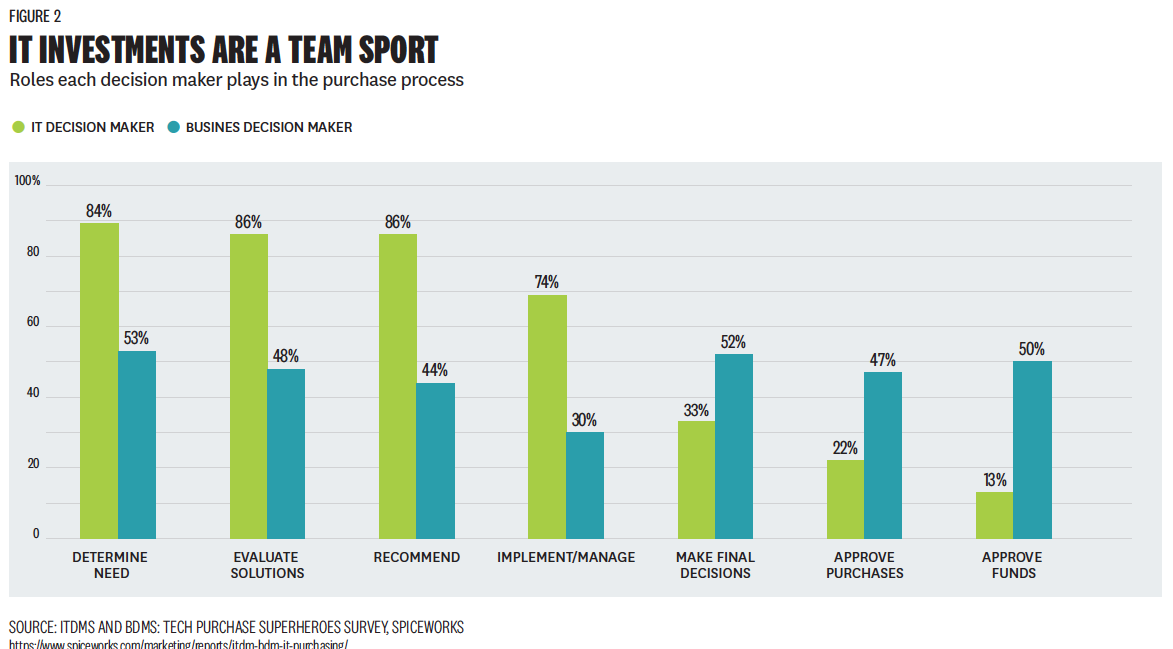

Increasingly, IT and line of business heads are working closely together to make IT investment decisions. The division of labor effectively balances the expertise of each of the two from identifying needs and new technologies to seeking business unit approval before making the buy.

Knowing When to Act and How

As the digital transformation of business began to pick up speed, many organizations outside the technology sector weren’t prepared. Instead of meeting new customer needs, they mostly stuck to their knitting—and promptly disappeared. The lessons weren’t lost on alert CEOs, who are now keenly aware of the speed of change and customer expectations.

“The advent of exponential technologies has raised awareness,” says Nick Davis, vice president of enterprise solutions and corporate innovation at Singularity University. “Executives understand that technologies that seem to be moving slowly may, in fact, be on an exponential trajectory with hockey stick growth just around the corner.” Technologies such as robotics, 3D printing, and AI may seem to be moving slowly, but they are advancing at a fast clip, according to Davis.

Chatbots and natural language processing are prime examples of potential quick growers. For example, in the most recent content involving the Loebner Prize, a German organization that presents awards to technologies that best exhibit human thinking and behavior, judges posed a range of questions that the bots could often answer—everything from ‘how old are you?’ to ‘when might I need to know how many times a wheel has turned?’ (Being able to answer the latter is a giveaway that one is chatting with a bot and not a person, who most likely couldn’t answer the question.)

As executives seek new ways to chart the future, Davis says they need to change their approach to strategic planning. The traditional way of doing such planning is to analyze macroeconomic factors and then project how they will affect the business in the next three to five years. This approach is giving way to new practicable means of sizing up the future, regularly testing assumptions, and steadily building new capabilities to address the needs the tests indicate.

“You can look out 10 or 20 years and make some reasonable assumptions about what customers will expect and how technology can meet those needs,” says Davis. He points to electric and self-driving cars, renewable energy, and huge growth in the use of AI. “Companies in industries affected by these technologies are quite aware of the massive changes underway,” he says. “Utilities understand that ‘smart’ houses and buildings will fundamentally change their businesses. Health care providers are already speculating about how electronic medical records and gene editing will create demand for individualized medicine.”

The key is to posit what the future will hold and use techniques such as agile development to keep pace with customer expectations and the technologies that can meet them. Hagerty, a Michigan-based company with its roots in specialty insurance products for classic and collectible cars, has been conducting scenario planning exercises every few years practically since its founding in the 1980s, according to its CEO, McKeel Hagerty. The sessions dig into technologies and emerging customer needs that could affect the business in the future. Many strategic decisions have emerged from these sessions that have led the company to become an automotive lifestyle brand for classic car enthusiasts—well beyond core insurance products. To keep close to enthusiasts’ needs and changing markets, the company created the Hagerty Drivers Club, which offers special events, a magazine and other benefits with its paid membership.

Although senior management doesn’t always agree about what the possible scenarios reveal, they have spotted major trends in their nascent stages. For example, Hagerty spotted the emergence of the sharing economy more than a decade ago. Recently, a company launched a platform where people could rent classic cars by the hour. Having kept pace with the details of such a platform business, Hagerty bought the company and can now provide another service to their clientele.

To keep its finger on the pulse of changing customer needs and emerging business models, Hagerty uses agile development sprints. “Businesses should regularly conduct quick experiments with new technologies and customers to understand how needs are changing,” says Hagerty. “Even more important, conducting sprints builds capabilities with new technologies so companies won’t be caught off guard when they need to scale up quickly.”

Building the New While Running the Old

Davis believes that these challenges will become more straightforward over time. If a business has a clear point of view about what the future holds and is using agile experiments to keep up with market trends, discovering and using new technologies and market insights will become part of the cultural norm. Moreover, new technologies offer significant opportunities to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of legacy businesses. AI, for example, can help strengthen everything from marketing analysis to cyber security.

Even though new ideas may be taking hold within established entities, companies will still want to work with startups. Joerg Niessing, a professor at INSEAD, advocates that established companies shouldn’t focus on buying startups as they have long been advised to do. Instead, they should create permeable boundaries between their businesses and the startup community and charge key internal personnel to work with the startups and thus establish a beachhead for new ideas in the organization. Startups are seeking customers, so enterprises should make them company suppliers.

Simplifying the Math

Boston Scientific’s Eddy underscores the challenge of massive amounts of data being generated and matching it with people who want to harness it. The result is often constant debates and demands for new reports, but few decisions.

Robert Morison, coauthor with Thomas Davenport and Jeannie Harris of Analytics at Work and lead faculty at the International Institute for Analytics, says that to avoid constant data debates, organizations should be clear about when they really need ‘a single version of the truth.’ “When you are personalizing outreach to customers, you need a database with one accurate version of information about them,” he says. “You can’t make mistakes that make customers feel like you don’t know them or are wasting their time.”

However, when trying to track and spot changing customer needs and market trends, businesses can use much ‘messier’ data, especially in the discovery mode. “When companies are looking for patterns and trends, they really only need directional data. Everything doesn’t have to be perfect, especially if the company is using outside data that can be difficult to match to internal sources. Even if the data is imperfect, patterns in customer and market behavior will still be clear.”

Morison also says that companies are getting better at deploying data and analytics staff. “I see analytics groups getting smarter and more disciplined about how they form teams,” he says. “They pull together data scientists, data engineers, business analysts, and other needed specialists. This allows data scientists to focus and not play multiple roles.” When data scientists can focus, the process can more readily address issues through expertise about how data can answer a specific question.

INSEAD’s Niessing echoes the sentiment and points out that business leaders are increasingly aware that they need to answer many of the same questions they always did. There is now just more data available to guide those decisions and increase their speed. “Executives still have to solve the same types of problems that they always have,” says Niessing. “They need to understand market dynamics and what customers really want and what competitors are doing—and then determine how the company should react.”

The HP Ways: Lessons on Strategy and Culture, https://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/the-hp-ways-lessons-on-strategy-and-culture.

Want to read the full report?

Questions? We’ll put you on the right path.